Startup Economic Lessons from Shen Yun’s Empire

What could a classical Chinese dance performance and The World’s buzziest Growth companies possibly have in common?

A lot, actually. Both aspire to change the world, both spend gobs of money to attract followers to their movements and both require the support of generous benefactors in order to survive. In this post, we will introduce you to the key players, explore the math behind the madness and learn why, in wars of attrition, patient capital can be the greatest .

Meet Shen Yun

If you have been to a city, you have seen the posters for Shen Yun.

If you haven not been to a city, let me pause to allow Shen Yun to introduce itself. From its website:

A Heavenly Gift

The culture of ancient China was divinely inspired. Shen Yun’s works reflect this rich spiritual heritage…

Shen Yun invites you to travel back to the magical world of ancient China. Experience a lost culture through the incredible art of classical Chinese dance, and see legends come to life. Shen Yun Makes this possible by pushing the boundaries of the performing arts, with a unique blend of stunning costuming, high-tech backdrops, and an orchestra like no other. Be prepared for a theatrical experience that will take your breath away!

I live in a city, New York, and Shen Yun’s posters are everywhere. They are in the entrance to the subway, they are in the subway cars, they are on buses, they are on buildings, they are on billboards, and they are even on your TV. When I drive home to see my parents outside of Philadelphia, they are on billboards on I-95. When I recently traveled to Mexico City, they rolled by me on bikes.

Given their omnipresence, they surprisingly advertise a limited show run of under two weeks. Which got me thinking: how does Shen Yun make any money?

Short answer: they don’t.

Longer answer: let’s dive into the numbers. Based on some rough calculations using theater size, show run, ticket prices, production costs, standard Out-of-Home (OOH) advertising rates, they lose about $1.4 million per run. Calculations below:

So far, so good! Just on the performances, Shen Yun turns a healthy profit.

Advertising is where things get ugly. Based on my assumptions, Shen Yun spends over $4 million advertising each run of its show, eating up all of the $2.6 million of Performance Profits and resulting in a Net Loss of $1.4 million for each run in New York City. This number doesn’t even include print advertising, but I may be off on the number of OOH campaigns Shen Yun runs, so it should come out in the wash.

Source: twitter.com/verbena_lemon

Put another way, Shen Yun’s LTV:CAC ratio is all messed up. The LTV:CAC ratio compares the Lifetime Value of a Customer (how much profit you can expect to generate from that customer’s purchases for as long as they patronize your business, generally assumed to cap out at 1-3 years) to the Customer Acquisition Cost (how much money in sales and marketing it takes for you to convince that customer to patronize your business). What a good ratio is varies by industry and business, but an easy rule of thumb is that 3:1 is solid. Let’s see what Shen Yun’s looks like:

Yikes. With an LTV:CAC below 1:1, Shen Yun can’t “make it up in volume.” Their survival must depend on someone backing them who is in it for something bigger than financial gains. But who would care so deeply about ancient Chinese dance that they would be willing to fund millions of dollars of losses for 13 years running, with plans not to shrink, but to expand to more cities?

Meet Falun Gong

The New Yorker ran an excellent piece on Shen Yun and Falun Gong (or Falun Dafa) in March, and I highly recommend that you read it if you want all of the details. For our purposes, though, we’ll dive into a very brief overview of Falun Gong. Founded by Li Hongzhi in 1992, Falun Gong quickly attracted tens of millions of adherents, with the Chinese government estimating 70 million adherents by 1999. As for its beliefs, the Jia Tolentino of the New Yorker writes it better than I can:

“Its stated central values are “truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance.” The organization’s Web site notes that the “Falun,” meaning an “intelligent, rotating entity composed of high-energy matter,” is planted “in a practitioner’s lower abdomen from other dimensions” and then “rotates constantly, twenty-four hours a day.” Most of the group’s practices fall roughly within the traditions of Tai Chi and Qigong, and the group itself can be situated within China’s long history of apocalyptic sects promising redemptive transformation, such as the White Lotus Society, which dates to the Ming dynasty.”

Beyond these basics, Li has been outspoken in his anti-evolutionary, homophobic, anti-Communist and anti-race-integration beliefs, and Falun Gong has been denounced by the Chinese Government. While many of his beliefs are abhorrent, for our purposes, it is most important to note that Falun Gong has a purpose for Shen Yun beyond making money. According to one Quora poster (caveat emptor):

“Practitioners themselves spend part of their income and time to engage in activities that resist the persecution, clarify the truth to people around the world, or they themselves establish media companies to clarify the truth about the persecution, as well as to uphold the moral values of society while solving their living problems. They do not ask for aid or funding for their activities, but I think in the process of clarifying the truth, many people, organization have recognized Falun Dafa is really good so many people have been practiced Falun Dafa or volunteer to donate to Falun Dafa practitioners’ activities.”

Limited Partners, or “LPs,” are the money behind a fund. They are the people who invest in the investors. While most LPs are institutions or wealthy individuals who expect a financial return from their investment, Falun Gong’s LPs are essentially their volunteers who donate their time, skills and efforts to spread what they believe to be the truth and resist perceived persecution. According to the Guardian, local Falun Gong followers actually raise the funds needed to advertise and put on the show. Falun Gong, and by extension Shen Yun, has some of the most patient capital in the world.

But what happens to companies with similar economics whose investors don’t have LPs with unlimited time horizons and no expectation of monetary returns?

VC Money and Consumer Subsidies

In 2017, Alison Griswold wrote A eulogy for the golden age of VC-subsidized meals, which is finally over for Quartz. In it, Griswold explains how the food delivery funding cycle is supposed to work:

“Funding in food delivery is supposed to be a virtuous circle. Customers who are drawn in by coupons are supposed to be won over by the convenience and quality of the service. They become regular users, placing more orders more often, until the value of their spending exceeds the money the startup invested to win their loyalty. The startup tells investors about its soaring user and order numbers, and the lifetime value of its customers, and they award it even more money, which goes into more discounts and subsidies, and so on and so forth.”

Hello, LTV:CAC ratio, old friend. “Value of their spending” = LTV. “Money the startup invested to win their loyalty” = CAC. Griswold was writing about food delivery startups, because in 2017, food startups were dying faster than King’s Landing residents (spoiler alert). :wave: Sprig. :wave: Maple. :wave: SpoonRocket.

In the most viral Annual Letter this side of Omaha, Social Capital’s Chamath Palihapitiya writes about “The Accelerating Treadmill of User Acquisition.” Palihapitiya writes that, “When the VC industry invests capital into fast-growing startups today, the plurality, if not the majority, of invested capital will go into user acquisition and ad spending, for better or worse (usually worse).”

Glad you asked, Andrew. According to Palihapitiya startups spend almost 40 cents of every VC dollar on Google, Facebook and Amazon (and SF rents are upwards of $80/sf, meaning $15-20k per employee per year). But if companies are successful at attracting customers and building economies of scale and network effects, is that a problem?

Palihapitiya thinks that it is, and frames the problem through a game-theoretical lens: Spending this much on user acquisition to grow quickly and own a market works when just one company in an industry pursues that tactic, but when everyone behaves that way, “ad impressions and click-throughs get bid up to outrageous prices by startups flush with venture money, and prospective users demand more and more subsidized products to gain their initial attention.”

Because of the mechanics that Palihapitiya points out, the same pattern that we saw in the on-demand meals space emerges throughout the startup landscape, particularly in very crowded and competitive environments.

When DTC Is Just a Justification to Spend More on Customer Acquisition

Direct-to-Consumer (DTC), or Digitally Native Vertical Brand (DNVB), companies have been becoming unicorns at a nearly weekly clip in the past year. If you use Instagram and fall into the DNVBs target demos (affluent, youngish), you have been bombarded with ads for new products across consumer categories: sneakers, mattresses, cashmere, toothbrushes, sunscreen, sunglasses, bathing suits. The list goes on. Aside from the companies who are truly innovating, many of which appear in McNamara’s unicorn list, most of the thousands of smaller DTCs operate under the conceit that they can make the same product, but apply brand and marketing alchemy to build customer relationships and, ultimately, profits.

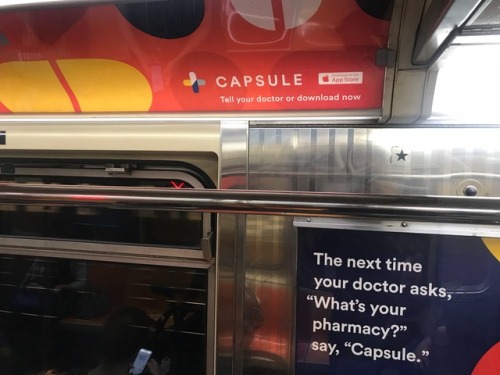

As Caldbeck points out, though, instead of fully understanding and innovating on the value chain enabled by the new model, most DTCs burn VC money in the form of marketing spend and lower pricing in order to acquire customers. Seemingly the only group that runs more OOH advertising than Shen Yun is the recently-funded DTC startup. There’s even a tumblr from Shai Goldman dedicated to NYC startup ads.

OOH advertising like the ones seen above are expensive, untargeted and notoriously hard to track. If you run a good campaign, you will likely see a spike in site traffic without being able to directly attribute it to the campaign. But they present another challenge: they attract a wide variety of people to your site, people who may or may not be anywhere near your target demo or have a real, ongoing need for your product.

Since many of these new customers were attracted by slick images and an offer to try the product at a discount using promo code “SUBWAY” (who among us hasn’t cycled through apartment cleaning services based on escalating subway ad discounts?), many of the smaller DTCs are likely to face the same issue that Shen Yun’s unit economics face: a low or non-existent repurchase rate means too low of an LTV to pay back the CAC. Instead of building movements, the new army of small DTCs may end up losing a lot of VCs (and their LPs) a lot of money, but not before the rest of us benefit in the form of new wardrobes, better skin and a better night’s sleep.

And then there’s the granddaddy of all VC-backed customer subsidies…

Uber vs. Lyft and EveryoNE’s (Subsidized) Driver

Ride-sharing company Lyft went public in March 2019, followed two months later by its largest competitor and industry-leader, Uber. Over the course of their competition, Uber and Lyft have resorted to gloves-off battles for drivers, going so far as to have employees call and cancel rides on their competitor’s app to frustrate drivers, and hailing competitor’s cars only to use the ride to convince the driver to switch to their platform.

On the rider side, the battle has been more familiar and straightforward: both companies subsidize rides to lure riders away from the other. In 2018, Uber spent $3.2 billion on Sales & Marketing, the category that includes rider discounts, while Lyft spent over $800 million on Sales & Marketing, not including $540 million in driver, rider, and passenger promotions, which they deduct from revenue. To be clear, this is not Uber and Lyft investing profits back into customer acquisition. In 2018, aside from a one-time gain, Uber lost $1.8 billion. Lyft lost $911 million.

Just like Falun Gong subsidizes Shen Yun’s losses in an effort to attract more followers, VC money, and now public market money, subsidizes our Uber and Lyft rides in an effort to attract us to their platform and away from the other, under the premise that 1) network effects matter in ridesharing - more riders —> more drivers —> more riders, etc etc, 2) the companies will be able to squeeze more LTV out of these customers, either through increased usage of the core product or bundle of other products, such as Uber Eats, and 3) autonomous vehicles will save the day and lower costs to the point that the unit economics of each ride are more attractive.

Thus far, however, competition-based subsidies have left the public markets scratching their heads, and some later-stage VCs and employees underwater on their investments.

Live Look at Public v. Private Market Investors

and their opinion of startups using their cash to subsidize consumers’ lifestyles.

So What have we learned?

While their ultimate goals are certainly very different, both Falun Gong and VCs are betting that if they invest in customer acquisition now, there will be a long-term payoff. For VCs, that payoff is either that a) the acquired customers’ LTVs grow to the point that the businesses’ economics make sense or b) their investment exits before unsustainable economics bring down the company. For Falun Gong, that payoff is a growing number of adherents and a global understanding and appreciation of their worldviews.

Ideas are only as strong as the economic models supporting them. Falun Gong and Shen Yun have the world’s most patient LPs - volunteers and adherents who are committed to changing the world. While Silicon Valley trumpets the same mission, VC LPs are not philanthropists, and they will only subsidize the products and services we consume for as long as they can reasonably expect a positive financial outcome.

With performances lined up in a record-high 130 cities, Shen Yun is just getting started. Meanwhile, with Uber and Lyft’s sobering IPOs, the startup subsidy dance is drawing to a close. Chamath Palihapitiya and Sun Tzu would agree: “the supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

Every week, I write a fresh essay that uses pop culture to simplify strategy, economics, and finance and explain current business trends. Get them first by subscribing to my weekly newsletter, Not Boring.